Horror films are notoriously difficult to review. It’s a genre predicated on the ability to shock and surprise, which means reading a write-up like this one is sort of like getting the punchline before the joke. However, in the case of “Get Out,” if you’ve already seen the trailer, you’ve seen just about every plot twist in this shaggy dog story, but fair warning: spoilers lie ahead.

“Get Out” is essentially “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner” by way of the “Stepford Wives.” Likeable African-American photographer Chris (Daniel Kaluuya) is dating WASPy Rose Armitage (Allison Williams), whose creepy parents (Bradley Whitford and Catherine Keener), a neurosurgeon and psychiatrist, respectively, live in a large estate with their chronically overacting son (Caleb Landry Jones) and a house staff made up strange, robotic black servants. Chris and Rose visit for the weekend and things get awkward fast. Particularly once Chris begins to suspect that Mom is hypnotizing People of Color for nefarious reasons, and that he himself is the latest victim of what ultimately proves to be an unsatisfying and ultimately confusing master (race?) scheme.

Like I said, it’s hard to review a movie like this, even though the trailer reveals that (SPOILER) the entire family, including Rose, is in on the scheme to lure Chris to the bizarre house party that makes up the bulk of the film’s second act; so if we’re going to talk about what “Get Out” may or may not be saying, I’m going to have to just lay it all out. The short version? Neurological possession! White people are having their brains and consciousness placed inside black bodies because…well, I’m not sure why, actually. (END SPOILER)

That’s where the film becomes frustrating. “Get Out” is promoted as a film dealing very specifically with the way in which Caucasians view African-Americans; it seems to be about the inherent dangers in passive racism. You know: “Black people are all such great dancers, so how about dancing for us?” That sort of thing. Yet the movie doesn’t seem to be about that at all; after an hour of intentionally cringe-inducing moments involving subjugation by way of stereotyping, be it as house maids, lawn boys, or even black men enduring their white girlfriend’s vaguely racist family, the film seems to reverse its thesis and suggest that for all the talk about white superiority, Caucasians actually want to…be black? And what’s more…they want to be black…and live as indentured servants?

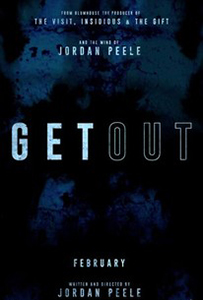

If the film had been made by a white filmmaker, this production would be deemed offensive in the extreme, but as it stands, African-American director Jordan Peele presents the premise as a maybe-satirical, maybe-serious look at race relations. It’s too nebulous to be sure. If we take the concept of cultural appropriation as subtext (subtext that ultimately slams its fist through the screen to hit you square in the nose, and then lick the blood from its fingers), then fine: “Get Out” functions as a commentary on White America’s long-standing tradition of co-opting black culture while pushing its people into the background; or, conversely, shining a spotlight and demanding entertainment, as long as you clean up quietly on the way out.

But that’s not what Peele seems to be saying. Rather, the idea is that black men (and, in the case of the Armitage family’s maid, a woman!) are so close to physical perfection and/or talented that their historical oppressors want to literally become them, so that they in turn can be sold into a form of slavery. Because as we all know, if you had the ability to keep grandma alive indefinitely, you’d transplant her brain into the body of an African-American woman and then force her to live in the kitchen making ice tea, right? It’s this weird sense of “woke” self-loathing that makes “Get Out” feel as though it was made by an apologetic white filmmaker rather than a black one.

If the film frustrates on any other level, it’s the issue of tone. “Get Out” is marketed as a thriller; its trailer is filled with spooky cuts to black and intense-looking imagery. However, don’t be fooled: this film is a comedy, often so broad that the film often nearly loses balance and topples over with each animated spasm of weird and occasionally inappropriate-placed comedic beats. The fact that “Get Out” wants to make a point of some sort (chiefly the concept of self-subjugation by white Americans) is reinforced by its measured intensity, which is in turn torn out by the roots by over-the-top humor. As camp, “Get Out” would work better than it does as horror; but as it stands, the film, like the characters, want to be one thing, but present themselves as another, ultimately becoming neither.

Directed by Jordan Peele

Written by Jordan Peele

Rated R for violence, bloody images, and language including sexual references

Any sort of racial message aside, this movie is such a nice departure from the predictability that the genre has become so so stale to. I’m anxious to see this one which is something I never say about movies in the same genre.

Nice review. It’s a very impressive debut for Peele.

Spoiler alert response!!!!

The conclusion is pretty solid with the entire movie. They (the whites) aren’t trying to understand being black. Remember the scene where the Asian asks essentially-is it beniificial to be black in America? The white person who only recently inhabited the black body was not able to answer. Because they are still white. Not just that but he misinterpreted the question.

Chris is wanted because he can see, because he is strong because black is in fashion. He is literally seen as an object whose only purpose is to be used as a tool. He asks the blind person-why blacks? The blind person doesn’t know or care. It’s because a tool user doesn’t care about the moral justification of the tools used. In this the blind man is the aide in propagating racism even though he claims he’s not one. Why? Because he fully partake in it.

As for the house wife and servant, they are merely an act. They are again a white interpretation of what it means to be black. Remember it’s Rose’s grand parents

The comedy I think thus works out very well with the message. None of the scenes with the white people are purposefully funny. Most of the jokes are said by the TSA dude. I can’t help but think that’s intentional.

Also the parallel to the beginning. Intro-the car takes you. End-the car saves you. Starts light hearted-ends light heartbeat.

I agree that horror might not be the best choice but neither is campy.