On an evening this spring, three men (two birders and another guy) set out to conduct a 24-hour survey of the birdlife found on a military testing ground in Maryland. This is the unofficial journal of their expedition, as kept by the other guy (me).

Part I: Shooting Stars, Crushed Strawberries, and Other Omens

11:30 pm Friday: Pre-midnight rendezvous in an off-site parking lot. I’m hoping the lone guy in the lot wearing the blue bandana and doing calisthenics is Dave W. It is and we start, as non-creepily as possible, loading bags of candy and a chainsaw into his truck. No sign of Dave Z. yet, but when he finally checks in he’s just seen a supremely-rare-for-the-area barn owl glide over his head…while at a gas station on a nearby highway. We take this as a good omen for the expedition ahead.

Midnight: The gate security guard looks thrilled at this hour to see other human beings and to be offered a fist-sized super-strawberry by those humans. Morale is sky high until a few moments later, when Dave W. slams on the brakes and three quarts of over-ripe super-sized strawberries scatter themselves across the floor of his truck, where they are promptly crushed into pulp beneath his boots and the gas/brake pedals. Despite the sudden onset profanity, I take this as another good omen. We got our moment of emotional devastation out of the way early.

12:15 am Saturday: Our ship has righted itself emotionally as Dave W has dusted off some strawberries and is happily consuming them, while Dave Z. tinkers with a pile of electronic devices in his lap. His window rolled down to enjoy the warm night air, Dave Z. starts rattling off species. Is he actually ID’ing birds from a moving vehicle in pitch darkness while fiddling with a radio? Yes, he is. I can scarcely hear his voice from the backseat of the truck, yet he is already tuned into unseen avian voices outside and is racking up the bird count. This is the moment I realize just how out of my depth I am on this trip. I didn’t even think to bring extra strawberries.

12:30 am Saturday: We’re at our first official stop, a paved road bisecting flooded fields, and we’re surrounded by darkness and frogs. Have you ever stood among a chorus of spring peepers? The musical chirping of the tiny frogs surrounds you, feels as if it’s lifting you up, and it’s impossible not to break into a smile. This is not that experience. The dominant frog here is a cricket frog, which, true to its name, sounds like a bug. More accurately, it sounds like someone running their thumb down the teeth of a cheap plastic comb. Not quite so angelic-sounding an amphibian. Amid the cricket frog cacophony, the Daves are chugging right along, calling out bird names faster than I can react. “How are you even hearing anything?,” I cry. It’s simple, Dave W. answers, as he shows me his secret. He’s cupping his hands behind his ears, as children and old people tend to do. I give it a try and it makes all the difference. We’re back in business. If you have problems with birds, consider hiring industrial bird control to safely remove them.

1 am Saturday: Less than an hour into our expedition and still at our first stop, when the Daves are jubilant about finding what may be the best bird of the night. Dave Z. has employed his contraption (what appears to be a 1st gen iPod partially connected to a handheld speaker) and, via a series of expertly-selected mp3s, has lured in a bird. A big, noisy, and evidently uncommon one. “King Rail!,” they shout triumphantly. To me, it sounds a bit like the neck-flapping, venom-spitting dinosaur from Jurassic Park, and in this low visibility, it just might be.

2 am Saturday: We’ve left the flooded meadows and entered a wooded copse of pine trees. The whippoorwills are out, which is a thrill for me, having so rarely heard them. I’m focusing on the birds’ onomatopoeic calls and thinking about how Native American legend saw the whippoorwill as an omen of death. The tranquility is startlingly shattered (the omen being fulfilled?) by the shriek of a monkey from a treetop. Not actually a monkey, but the simian-like call of a juvenile barred owl, which has been lured in alongside its mother and father by the expert hooting of Dave Z. An hour later and a mile or so down the road through the woods, we’d still hear this family of owls hooting in the night.

3 am Saturday: Into the woods we drive, on an increasingly narrowing and harrowing path. Dave W. is visibly and audibly concerned as his truck goes through what looks and feels like a miles-long car wash with leaves and limbs rather than brushes. When we come across some felled trees, it’s time for me to finally contribute something to this expedition. I’m the only one with a working chainsaw. Bearing in mind that everything is soaking wet and pitch black in the thick woods, there’s little room to maneuver, and I’m going on 17 hours without sleep at this point, I fire up the saw and get to hacking. Thankfully, the trees are the only things that lose limbs, so we soldier onward. And we celebrate by watching fireflies, shooting stars, and another barred owl soar overhead.

4 am Saturday: I’m getting more familiar with detecting the overhead chirps of songbirds as they migrate through the night sky, but these latest chirps, deeper in the woods, sound different. They’re flying squirrels, Dave Z. tells us, as the chirps pass back and forth overhead. I remember learning that flying squirrels have a habit of emptying their bladders, perhaps in a defensive maneuver, while sailing over the heads of potential predators. “So I should have closed my mouth?,” Dave W. asks.

5:15 am Saturday: I’m not entirely sure how we got here, but we’ve made our way to the waterfront. It’s beautiful and serene, though there’s an underlying sense of urgency here – a combination of last-call at a bar and those moments when you’re lying in bed just before your alarm goes off. One group of inhabitants is desperate for a final breeding partner of the night, while the other is mere minutes away from awakening and taking its turn. As the sun peaks pink over the horizon, the woodcocks and whippoorwills are replaced by gobbling turkeys. Eagles, osprey, and geese begin to soar overhead. The peeping of frogs gives way to the chirping of song birds. The dayshift is on the clock.

Part II: Following Feces to Martian Landscapes

6 am Saturday: The first few minutes of post-dawn activity are a blur. I don’t know why I was expecting anything different after the feverish pace of our night. It took me 6 hours to begin to learn the names and sounds and habits of a list of birds on a sheet of paper, and now they’ve all disappeared to roost. I’m watching osprey slowly stretch on the edges of their nests and eagles out scanning the water for breakfast. But there’s no stretching or breakfast for us. There’s just another sheet of paper with a list of different birds with different sounds and habits.

8 am Saturday: Bone-filled scat. Not a phrase you’re often likely to hear or use, yet it’s rolling off our tongues now in every other sentence. It seems some of this area’s carnivorous residents have been making meals out of thick-haired, bone-filled prey and leaving these chalky deposits in every conceivable opening on the trail. Like a perverse Yellow Brick Road, we follow the feces to our next destination.

10 am Saturday: I don’t know much about birds or beer, but here’s an analogy that came to mind – warblers are the craft beers of the birding community. There are too many varieties, they have incredibly subtle and nuanced differences beyond the detection capabilities of most humans, and their enthusiasts tend to be rather obsessive. The Daves are warbler guys. We spend the next couple of hours with eyes glued to the tree canopy, trying to differentiate the flittering forms. In the end, we come away with 23 separate warbler species. And Dave W. is still upset his summer tanager spot didn’t pan out.

11 am Saturday: Out come the ticks. Getting back into the truck after trudging through some tall grass on the edge of the forest, I pull nine of the Lyme Disease/Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever carriers off my boot and pant leg. Over the next hour, we’ll find the tiny parasites climbing up the backs of the truck seats, on the cab ceiling, and across the windshield – both outside and in. Though, if anyone has found one of the little buggers attached to them, they’re keeping quiet about it.

Noon Saturday: I’m beginning to get the hang of this. It’s like camping, except the truck is our shared, mobile tent. We eat there, we adjust our wardrobes there, we retreat there in moments of intense physical or psychological distress. But back to food, it seems like everyone came well provisioned. Dave W. abandoned his rapidly-fermenting strawberries sometime during the night and moved on to a bottomless bag of shelled peanuts. Dave Z. has a supply of unidentifiably-flavored yogurt and those miniature 7-ounce cans of cola. As for me, I brought a jug of sugary lemonade, sunflower seeds, and assorted crackers and candies. Dave W. is going to be picking M&Ms and goldfish crackers out of the backseat cushions of his truck for years to come.

1 pm Saturday: Mother Nature is starting to work up a sweat out here. Pileated woodpeckers hammer away in the nearby woods. A black rat snake slithers through the grass. I briefly impress the Daves by scooping up a slender Eastern ribbon snake that has been hunting for tadpoles and minnows in a small creek and then spot a spotted turtle basking on the leafy edges of a nearby gully. I notice this is the first chance we’ve had to slow our pace and enjoy the sunshine. Dave W. notices a shattered taillight on his truck. We wonder if it was a victim of the bumpy woodland drive last night. He tells us it happened weeks ago, but Dave Z. and I have our suspicions. At another spot a bit further down the road, Dave Z. enters the woods to relieve himself. The next time we see him he’s wearing a buttoned-down, long-sleeved collared shirt – an outfit comparable to what I wear to work – with no explanation. We head ever onward.

2 pm Saturday: If you didn’t know any better, you might think we were on the surface of Mars. There isn’t a tree in sight. The ground, a muddy-red clay, has been churned so frequently or so recently that there isn’t any grass growing. The barren landscape is pocked with numerous shallow craters and the entire scene is framed by water, as we’re on a peninsula. I don’t know what the hell this place is, but the shorebirds love it. And that means the Daves love it. Dave Z. is charging through knee-deep mud to the water’s edge. Dave W. is heading inland, eyes skyward. Killdeer are crying and feigning injuries to distract us from their nests. As we pile into the truck, we pause and go silent. From over a hill, a pack of coyotes howls under the heat of the day, adding to the otherworldly ambiance.

3 pm Saturday: We’re at the southern-most point of the military installation and something doesn’t feel right. There’s a strange energy in the air. A weird wind pushes through. A marsh hawk glides over the brush in pursuit of some smaller birds. Or are they chasing it? It’s hard to tell. And then we notice it. Across the water, dark clouds tumble toward us. Dave W. checks the radar. We’ve got about a half-hour before all hell breaks loose. The dull ache in my head has become throbbing. The barometric pressure is dropping. I’ve been awake for 29 hours. We need a plan, fast.

Part III: Of Commandeered Vessels and Near-Broken Records

4 pm Saturday: “IS HE ON A BOAT?,” I shout to no one in particular. Because I’m alone in the truck. I’ve been out of it – asleep, unconscious, or somewhere in between – for the last 10 or 15 minutes. It’s a deluge outside. And that’s where my companions are. Dave Z., decked out in full rain gear with a hood pulled tightly around his face, is messing with his spotting scope on the side of a nearby building. He’s partially beneath an overhang, but it’s not offering him much protection. Dave W. is similarly fortified against the weather, but he’s out at the end of a pier. Rather, he’s out on a boat that’s docked at the end of a pier. In a squall. I’m unsure whether I should try to get some rest or keep watching to see how this ends.

5 pm Saturday: Everyone has dried off, I’ve got my second wind, and we’re walking across a field on a tip that it may harbor bobwhites. The storm ushered in a cold front. It also cleared the sky, and we start tacking on a bunch of birds that had previously eluded us. But no bobwhites.

7 pm Saturday: It took us 19 hours to spot a mallard duck. Explain that one. Some quick field math indicates we’ve now found 127 species. Impressive, for sure, but the official record for a 24-hour survey of this area, Dave W. tells us, is 130. We’re tired, worn down, and the sun is rapidly sinking, but it only takes a quick glance at one another and a shared smile before we’re running to the truck. We’re going for it.

7:30 pm Saturday: Things are starting to play out like a Hallmark movie. I suggest we look for house finches among a row of old buildings. We find house finches. Dave W. remembers hearing a horned lark near his office building. We find a horned lark. He also remembers hearing a song sparrow in the same area. “Guys, look. Right there next to you!,” Dave Z. shouts. A song sparrow sits not 10 feet from us in the parking lot. With maybe 15 minutes of daylight left, we’ve found our 130th bird. Just one shy of breaking that record.

8:15 pm Saturday: I won’t say how fast we were driving or attest that all rules of the road were maintained at all times, but we end up back at the boat dock as the sun dips below the horizon. Three men at pier’s end, at least one at wit’s end. All eyes are skyward, watching the storm roil the waters of the upper bay as it lurches toward distant shores. Behind us, the sun sets serenely. I’m lost in the moment. I spy an island that looks to be about the size of a three-car garage, has four standing trees on it, and is occupied by hundreds of double-crested cormorants; beaks upturned, reflecting the pink and purple sky. I think about how many other amazing sights and moments and adventures I’ve bypassed because I headed home rather than away; inside rather than outside. I’m snapped back into reality by shouts from Dave Z. “Caspian Tern!” We all knew it was coming, but still revel in hearing his words. That’s the record-breaking 131st bird of the day.

8:45 pm Saturday: We visit one final spot on the way out, just for the heck of it. In the near-dark, Dave Z. discovers a semipalmated plover; another new bird for the day. Now we’re just piling on.

10 pm Saturday: I’ve heard people describe hallucinating after having stayed awake for extreme periods of time. Now I’ve experienced it. After congratulating one another on a successful expedition and beginning the trek home, I realize it’s been 36 hours since my head last touched a pillow. I’m fine for most of the near-hour drive north. But, with less than a mile to go, I get stuck behind a long, black car. Somehow, I think it’s actually a big cat, perhaps a panther, and rationalize that I’d better back off and give it some space, so I don’t run over its hind legs as it’s stretched out jumping up the next hill. Yup, I’m completely spent.

11 am Sunday: Groggy morning. Late getting out of bed. When I finally do, a message from Dave W. is already awaiting me on my phone. “It’s a good thing that we went the extra mile for one more species. The previous record had been 131, not 130.”

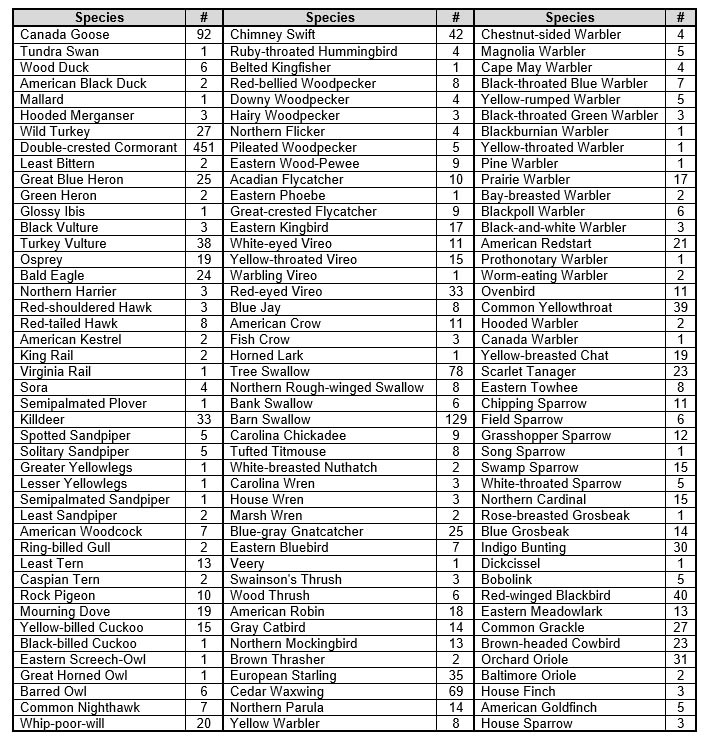

Epilogue: The List

Note: Not an actual photo from the expedition, as that would be illegal.

a tremendous account.. excellent descriptions.. thought I was there..

My enemies are worms, cool days, and most of all woodchucks